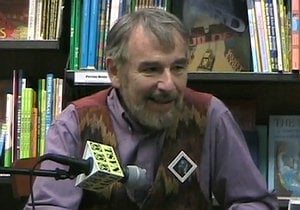

Dr. Richard Greeman is an academic, writer and a political activist since the late 1950s. He completed his Columbia Ph.D in April, 1968 while occupying the University as one of the radical student leaders of the student strike. Dr Greeman has taught at Columbia, Wesleyan and the University of Hartford and is best known for his highly acclaimed translations and studies of Victor Serge, the Franco-Russian writer and revolutionary. He is one of the founders of the Praxis Research and Education Center an independent, voluntary collective in Moscow, Russia. His book "Beware of Vegetarian Sharks", a collection of powerful as well as humorous essays, is available online through Lulu at http://www.lulu.com/product/paperback/beware-of-vegetarian-sharks/5429514 He lives in Montpellier, France.

ECOCLUB.com: In your recent book "Beware of Vegetarian Sharks", you hope that "the billions can unite in solidarity in order to ‘lift the earth' before it succumbs to capitalist ecocide". Given that Tourism already covers a big and growing chunk of the world (capitalist) economy, is contributing to ecocide thanks to mega-resorts, pollution and travel emissions, with increasing corporate concentration and a record of 'informal' labour exploitation, what could the billions do in the context of tourism, both as travellers and travel providers?

Richard Greeman: Robert Louis Stevenson said it all: "Tread lightly on the earth's thin crust." Those of us who are privileged to travel in the world should use these opportunities to make and maintain person to person connections with people and organizations in host countries in order to spread information and create links of solidarity.

ECOCLUB.com: In international Tourism, too, there are the equivalent of vegetarian sharks, peddling corporate social responsibility, carbon offsets, pseudo - "responsible" and "sustainable" (through exploitation) tourism, greenwashing certification schemes and the like. Travel also provides escapism, cheap and fake dreams of a lavish lifestyle for a week in the post-colonial / neo-colonial global south. How optimistic are you about the possible emergence of a sizable, truly alternative, ecosocialist current in Tourism?

Richard Greeman: As a US citizen, I used to be ashamed of the 'Ugly Americans' who showed up in Europe on tours, talked loud and expected 'foreigners' to understand them, demanded their local foods, etc. But in the last twenty-odd years, living as I do in Europe and traveling extensively, most of the Americans I have observed are pretty cool. Low key, modest, open to learning and making friends. If this huge transformation can take place, then there is hope! The question is, can we provide truly alternative, solidarity tourism that will build positive understanding and connections?

ECOCLUB.com: Indeed, in which key ways would such an alternative, ecosocialist, tourism differ from the current, capitalist varieties? For example, could there be a simple, universal answer to the question "who should 'ideally' own & run a hotel"? A local, self-managed, worker's collective for example and/or a family perhaps?

Richard Greeman: Sounds good to me. I bet lots of alternative-style tourists would be delighted. And it would be a survival strategy for Ecosocialist militants in poor countries, leaving them free to speak out, organized, etc. Go for it!

ECOCLUB.com: Is Internationalism and interculturalism really compatible with preserving variety of languages, beliefs, traditions, customs, gender roles, when some are inextricably linked with nationalism?

Richard Greeman: You know, it was Woodrow Wilson, not Lenin, who came up with the 'self-determination of peoples' idea, but it seems not to have worked out as hoped. Every time an oppressed people becomes a 'nation', that is a state with borders, taxes, police and army, they turn around and start oppressing a minority or weak group WITHIN the new borders. The paradox of Israeli Jews oppressing Palestinians is only the most glaring example of this general observation. But we have the

Vietnamese, the Algerians, the Nigerians, and all the other newly 'liberated' governments oppressing their minorities. And worst of all the imperialist US/GB coalition invading Irak and Afghanistan in the name of 'self-determination'!

So instead of national rights - so hard to define - I am for human rights, as defined by the UN Universal Declaration. Respect for human rights includes gender, language, education, health, food, labor organizing and (most recently) water rights.

My rule of thumb as an internationalist:

ALWAYS work in solidarity with women or workers or farmers in struggle in places like Irak - sending aid, publicizing, pressuring our governments, providing safe havens for the persecuted etc. to individuals or organizations like the Iraki Freedom Congress (http://www.ifcongress.com/English/ )

NEVER choose sides in a fight between two nationalist oppressors, for example violent reactionary Islamicist militias VERSUS U.S. occupation forces. The enemies of our enemies are not our friends.

ECOCLUB.com: From your vast experience with civil society and political movements, and as proponent of (Victor Serge's) an 'Invisible International', how realistic is it to self-organise without leaders, parties, rigid structures?

Richard Greeman: I think it is the ONLY practical and realistic way to go. Here's my irrefutable argument:

1) AGREED: To be effective against GLOBAL capitalism organization must be INTERNATIONAL (Planetary).

2) OBSERVED: Every attempt to create top-down, hub-and-spokes type international organizations -- be they the 2nd (Socialist), 3rd (Communist), 4th (Trotskyist) and various attempts at 5th internationals -- have failed. All ended in betrayal or demoralizing sectarian fractional splits.

3) CONCLUSION: Time to try something new.

I can't give a 'blueprint,' but I can OBSERVE that ever since 1994 when the Zapatistas rose up against neo-liberal globalization (NAFTA) in 1993, a vast planet-wide movement has begun to emerge. World-wide protests generated by this network prevented the Mexican Army from wiping out the Zapatistas, and since then the planetary movement has grown from one (relatively successful) self-organized struggle to another, each foreshadowing enormous future potential.

Some examples: In 1997, union dockers in Liverpool, England were locked out by the bosses, a global boycott in solidarity with the Liverpool dockers turned away ships carrying 'scab' (non-union) goods in California and Japan. Imagine the potential of a global boycott of BP in 2010!!

Similarly, in 2003 there was a planetary demonstration in fifty-plus countries against Bush's planned attack on Irak. The NY Times headlined: 'A New Superpower Is Born: Global Opinion'. Shades of France in 1789.

And then we have the examples of the highly effective mass protests against neo-liberal globalization at Seattle, Cancùn and so on, organized via Internet. This is a tactic that enables the Billions to mobilize against the Billionaires on equal footing.

Finally, look at the growth of the World Social Forums, and the planetary organizations like Via Campesino that grew up around them. Here we have an 'actually existing' 5th International that brings together hundreds of millions of politically conscious activists all around the globe.

What pseudo-Leninist 'Internationale' dreamed up in a seedy office in NY or Paris could possibly match that achievement?

Best of all, this global network called the 'movement of movements' is nearly indestructible. No Central Committee to be arrested, or taken over by opportunists, or to split and murder each other, or to attach itself to one Great Power or another in the name of the lesser of two evils! Indeed, our emerging planetary movement, which appears chaotic only through the narrow perspective of the State-like top-down vision, is constantly correcting its course as various attempts or ideas succeed and fail in practice. So this collective wisdom à la Wikipedia turns out to be a more reliable compass for steering the world-wide movement than any imaginable Steering Committee.

The role of us Ecosocialists within this vast Invisible International is to keep insisting that time is running short for the planet, that you cannot separate the economic and ecological crises, that capitalism is the cause of both problems, and that any solutions must be planetary.

ECOCLUB.com: And finally, how optimistic are you about the current and future role of the Internet? Are you optimistic that it will remain devolved and more or less accessible to all, hosting, among other things, a "highly organized chaos of organizations, websites, networks" working for change, or will it gradually deteriorate into corporately-owned and state-monitored/censored hyper-Internets, due to commercial pressures and 'security' considerations?

Richard Greeman: Both tendencies exist. Our fight right now in the US is against Google and Verizon, who want to end the era of equal access (called 'net neutrality') and give an advantage to rich corporations over individuals and small groups like your's. But both tendencies will continue to exist until a) the billionnaires destroy the world or b) the billions, connected through Internet rise up and create a planetary society of equals.